The Red Fort: An Enduring Symbol of India’s Sovereignty and Freedom

-Muhammad Waris, Badshahnama

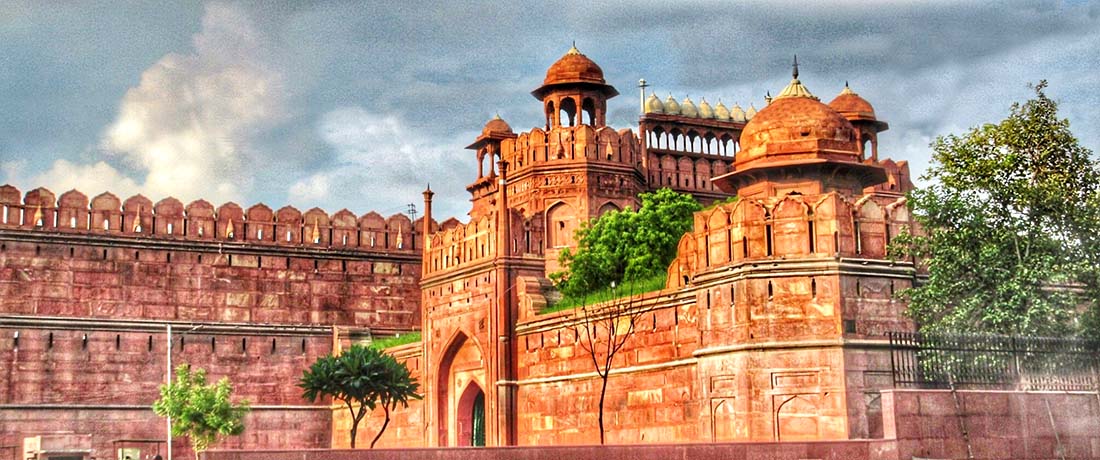

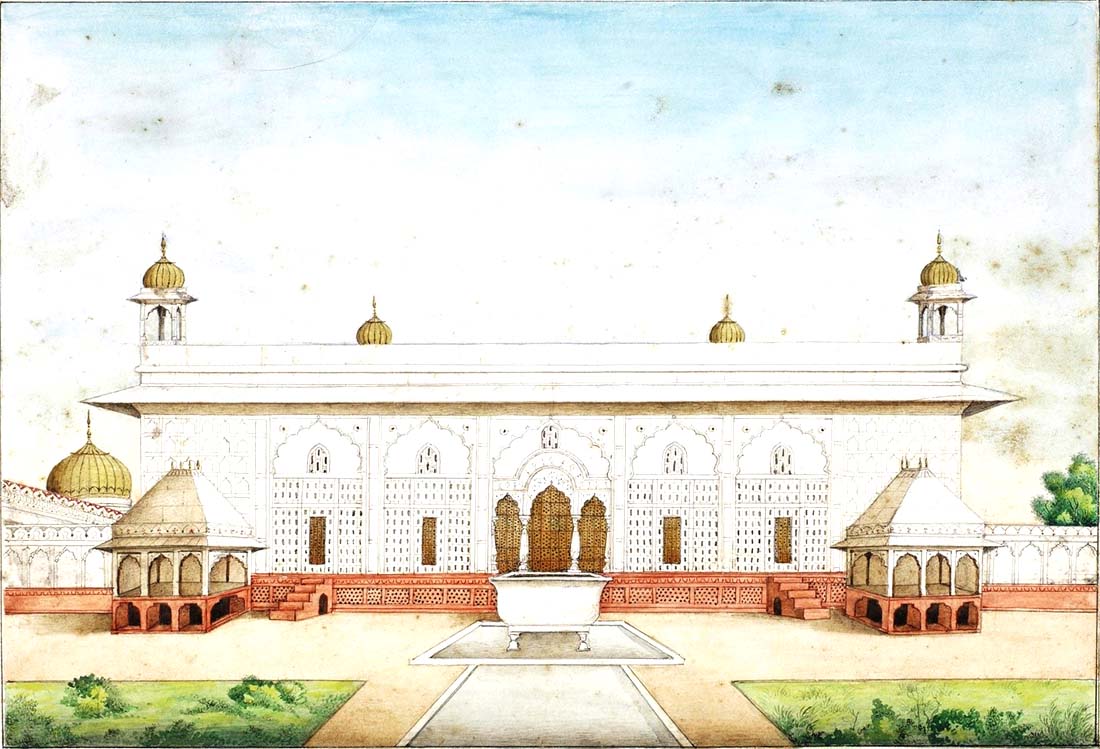

Front view of the Red Fort. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Red Fort or Lal Qila is an iconic monument synonymous with the rich political heritage, freedom, and sovereignty of India. Built in the 17th century CE, by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, this fort complex is one of the largest and grandest in India and is integrally connected to the vicissitudes of the political history of our country.

The Inception: A New City, Capital and a Citadel

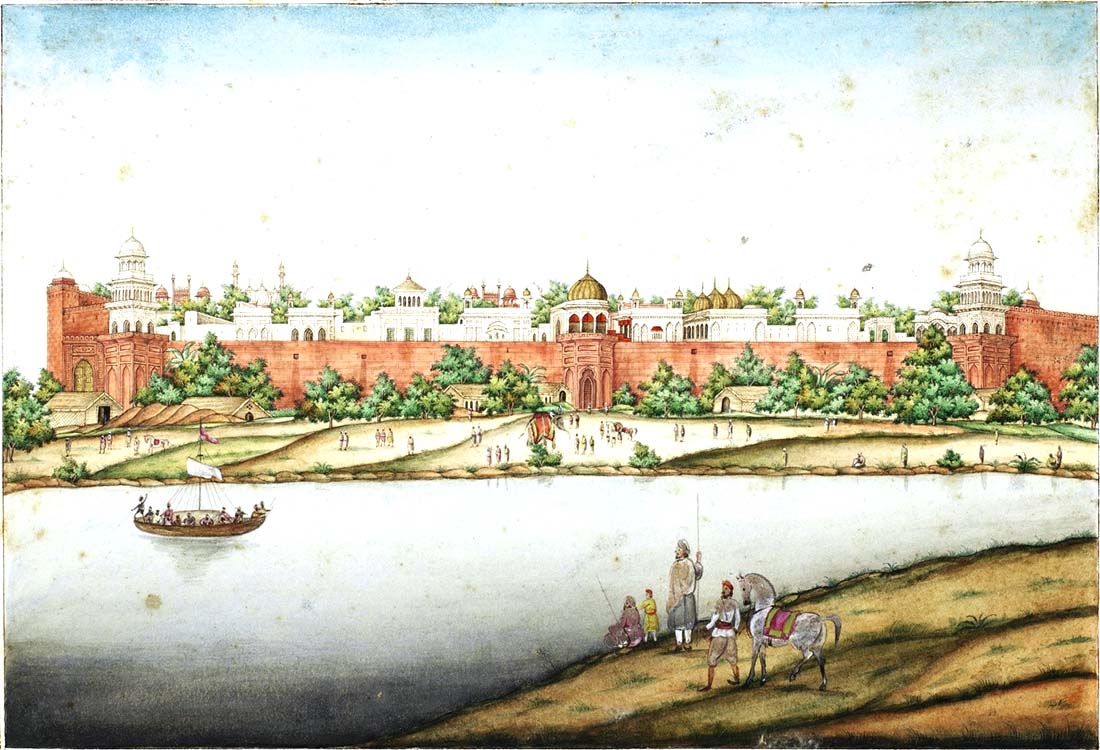

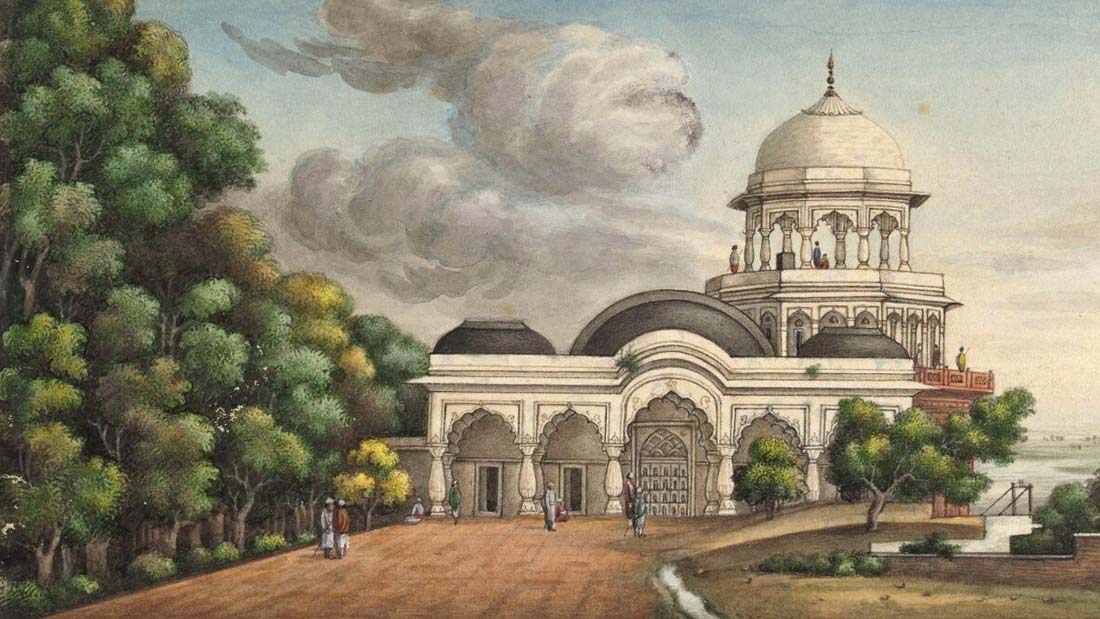

A painting of the Red Fort and the Yamuna river by Ghulam Ali. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Red Fort is located at the eastern end of Chandni Chowk, one of the oldest and busiest markets in Delhi. The origin of this market lies in Shahjahanabad, a new capital city founded by Shah Jahan. In fact, the Red Fort was designed as the nucleus of this capital city and as the prime seat of power of the Mughals. The establishment of the fort and the city was carried out in a planned manner and involved the best of architects and the choicest of resources. The site chosen for the fort was next to the older, existing fort of Salimgarh.

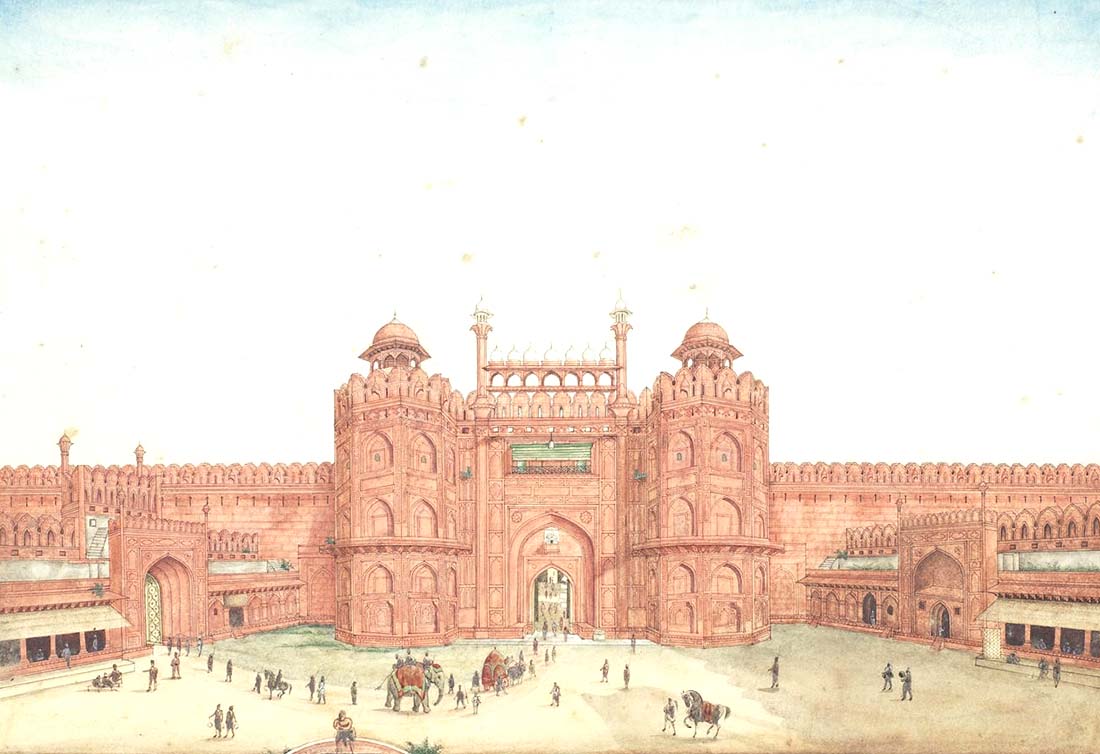

Lahori Gate, painting by Ghulam Ali. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The foundations of the fort were laid at an auspicious time in 1639 CE under the guidance of chief architects Ustad Hamid and Ustad Ahmed. Emperor Shah Jahan took a personal interest in the fort and guided the process of the on-going constructions. The major constructions were finished by 1648 CE at an approximate cost of one Crore Rupees at the time. The inauguration of the fort was marked with great pomp and festivities. Lavish gifts such as jewels, swords, large sums of money, mansabs etc. were distributed among the nobility to mark the occasion. The construction of the fort was a celebration of the political prowess, grandeur and artistic excellence of the Mughals.

The Architecture

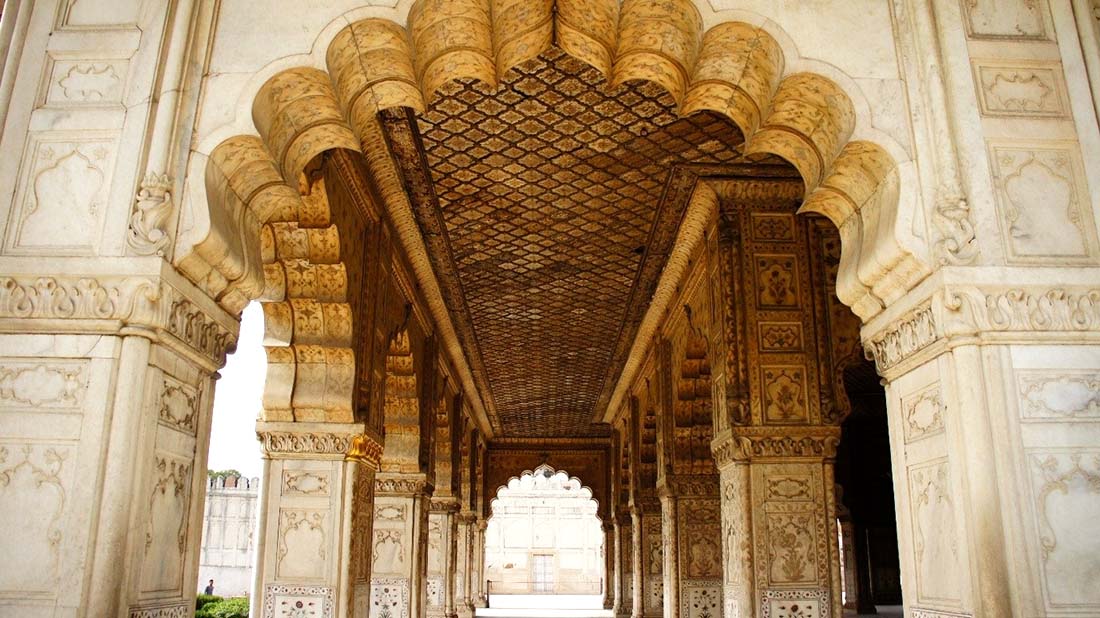

This splendid fort complex encloses an area of 125 acres. Its characteristic red sandstone walls are almost 3 kms long and are protected by a moat. The complex could be accessed by a total of 5 gateways, out of which three were prominent. The Lahori Gate, on the west, facing Chandni Chowk was the main entrance. The second important gate was Delhi Gate which was connected to the Jama Masjid via Faiz bazar. The Khizri Gate or the water gate was the entry used by Shah Jahan to inaugurate the fort after its completion.

Delhi Gate. Image Source: Flickr

A Physical Representation of Mughal Imperial Power

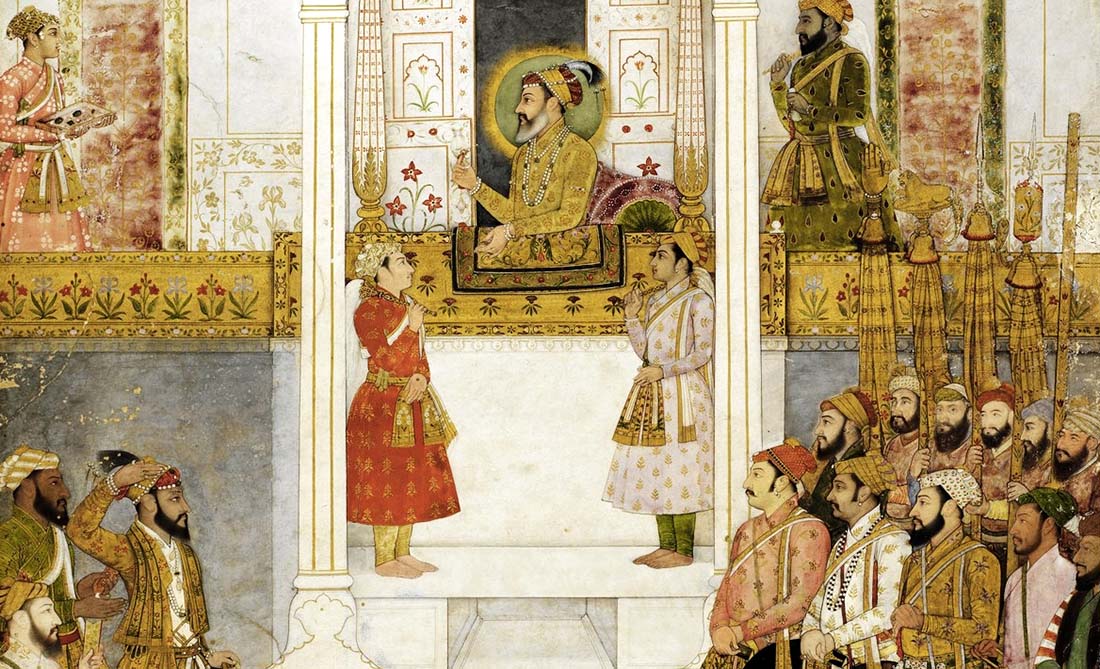

Shah Jahan holding durbar at Diwan-i-Am, 1650 CE. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Lahori Gate led to a covered market called the Chatta Chowk or Chatta Bazar. This market, a covered two-storied arcade, was built on the model of Persian bazaars. The Chatta Bazaar is well preserved and exists even today selling exquisite crafts items. The Chatta Chowk led to the Naqqar Khana or Naubat Khana. This two-storied structure served as the Drum Room to announce the arrival of the Emperor and other dignitaries. It is said that the Drum Room reverberated with music the entire day on the birthday of the Emperor and on other important occasions.

Chatta Bazar. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

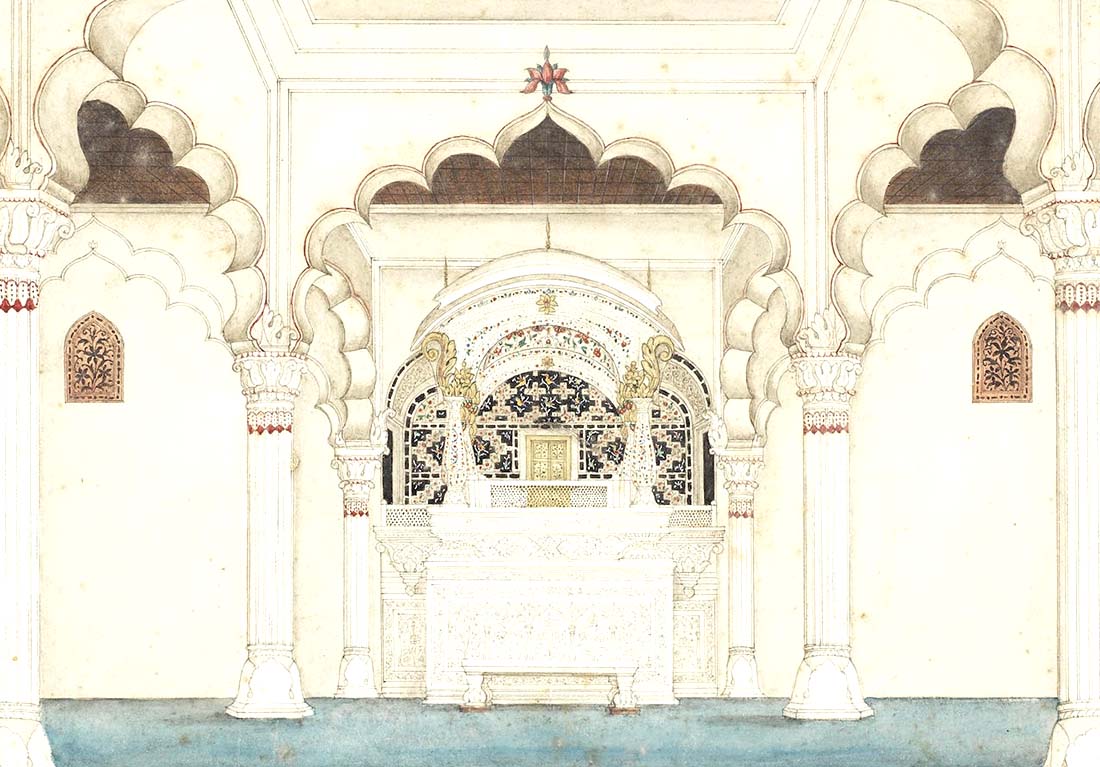

The Drum Room led to the Diwan-i-Am or the Hall of Public Audience where the Emperor gave audience to his subjects. This pillared red sandstone structure houses an exquisite marble throne set upon a high marble plinth. The wall behind the throne and the throne itself is embellished with motifs that establish the Mughal Emperor as a divine monarch. The wall is adorned with rare black marble plaques with intricate pietra dura work depicting animals, birds and floral motifs. It is held that this decorative work has been inspired by Italian art. The central panel, which lay right behind the emperor’s seating area depicts a figure of Solomon- venerated as prophet, king and judge. The geography of this part of the fort complex- from the Lahori gate up to the Diwan-i-Am, is planned and aligned in such a manner that the throne, and thereby the Emperor sitting on it, faces the city and his subjects as a guardian and a protector.

Canopied Marble Throne, Diwan-i-Am, painting by Ghulam Ali. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Royal Residences, Pleasure Palaces and Gardens

Shah Burj, painting by Ghulam Ali. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Next come the residential buildings of the complex which were placed alongside the river Yamuna. To the extreme north of this set of structures is the Shah Burj or the King’s tower. According to records, this structure used to be accessible only to the Emperor and the royal children. This structure was topped by a chattri which is now missing. To the south of the Shah Burj, one encounters the Hira Mahal, a white marble pavilion. Further south are two important structures which were originally considered to be part of a single complex: the Hammam or the Royal Bathhouse and the Diwan-i-Khas or Hall of Private Audience. Only select members of the royal family, nobility, and dignitaries had access to these exclusive and intimate chambers of the Emperor. It is said that the most important state issues were discussed here among the select few who could hold council. The Hammam houses exquisite tanks and water basins carved in marble and decorated with pietra dura. To the west of the Hamman is the Moti Masjid, a mosque built by Aurangzeb in pearly white marble for his personal use.

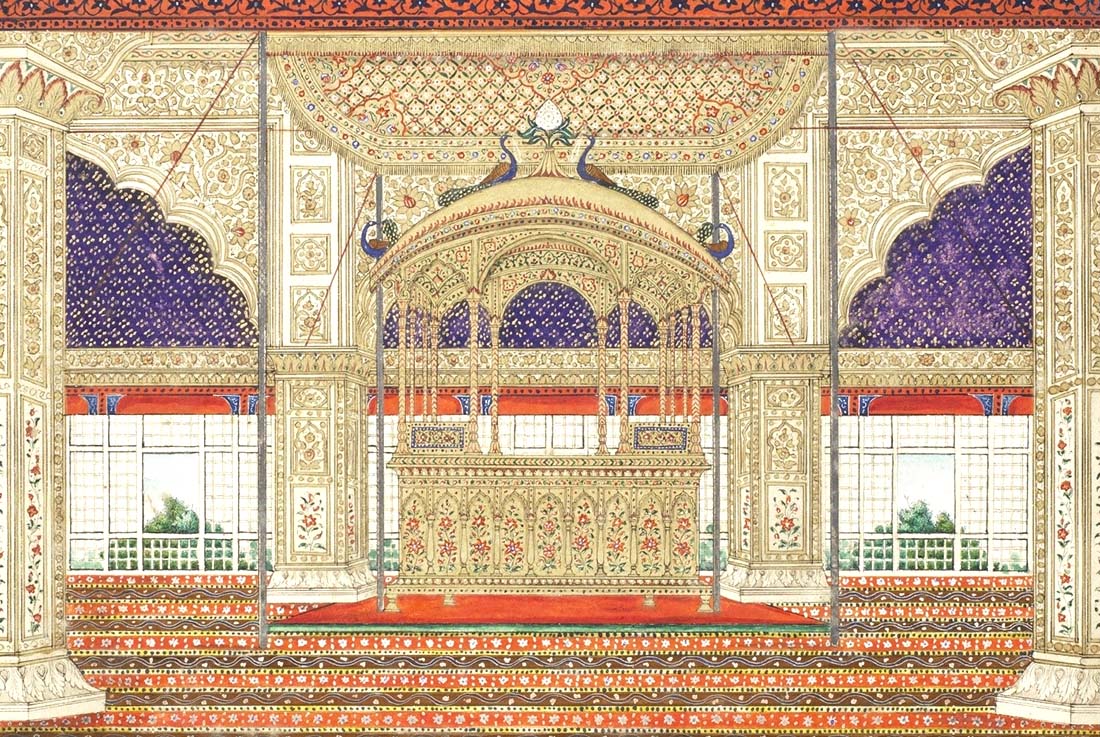

Takht-i-Taus or Peacock Throne at Diwan-i-Khas. painting by Ghulam Ali. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Diwan-i-Khas is one of the most spectacular buildings of the complex. Its ornate interior featuring ceilings gilded with silver and inlaid with gold and precious stones is unique. Marble pillars adorned with delicate floral marble inlay work enhance the aura of this structure. The Diwan-i-Khas is said to have housed the famous bejewelled throne: the Takht-i-Taus or Peacock Throne which was carried away by Nadir Shah during his invasion of 1739 CE. This gem-encrusted throne is also said to have been adorned by none other than the Kohinoor diamond. The walls of the Diwan-i-Khas contain the following verses which aptly describes its unparalleled beauty:

Agar firdaus bar roo-e zameen ast, hameen ast-o hameen ast-o hameen ast.

If there be a paradise on earth, it is here, it is here.

A view of the interiors of Diwan-i-Khas. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Adjacent to the Diwan-i-Khas are the Emperor’s residential quarters known as the Khas Mahal further divided into the Tasbih Khana or the private worship chamber, the Khwab Gah or the sleeping chamber, and the Baithak or the relaxation chamber. The Musamman Burj, a semi-octagonal tower with arched windows on the eastern wall of the Khwab Gah, was used by the emperor for the tradition of jharokha darshan or public appearance. It is believed that Bahadur Shah Zafar addressed the revolutionaries during the Revolt of 1857 from this very place. South of the Khas Mahal is the Rang Mahal, also known as the Imtiyaz Mahal- a pleasure palace used by the Emperor and the royal family for purposes of entertainment and relaxation.

Rang Mahal, painting by Ghulam Ali. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

A distinctive feature of the Red Fort complex is the Nahr-i-Bahisht or the Canal of Paradise. This stream was drawn from the river Yamuna and channeled through the Shah Burj. It then flowed in serpentine routes through the residential buildings and gardens of fort complex. It flowed through the central chamber of Khwab Gah beneath an elaborately carved marble screen, with the scales of justice inscribed on it. It further ran through the central aisle of the Rang Mahal and collected in a carved marble water basin in the shape of a blooming lotus, before making its way out again into the other buildings and gardens of the fort.

A view of carved marble screen beneath which the Nahr-i-Bahisht flowed, Khas Mahal. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

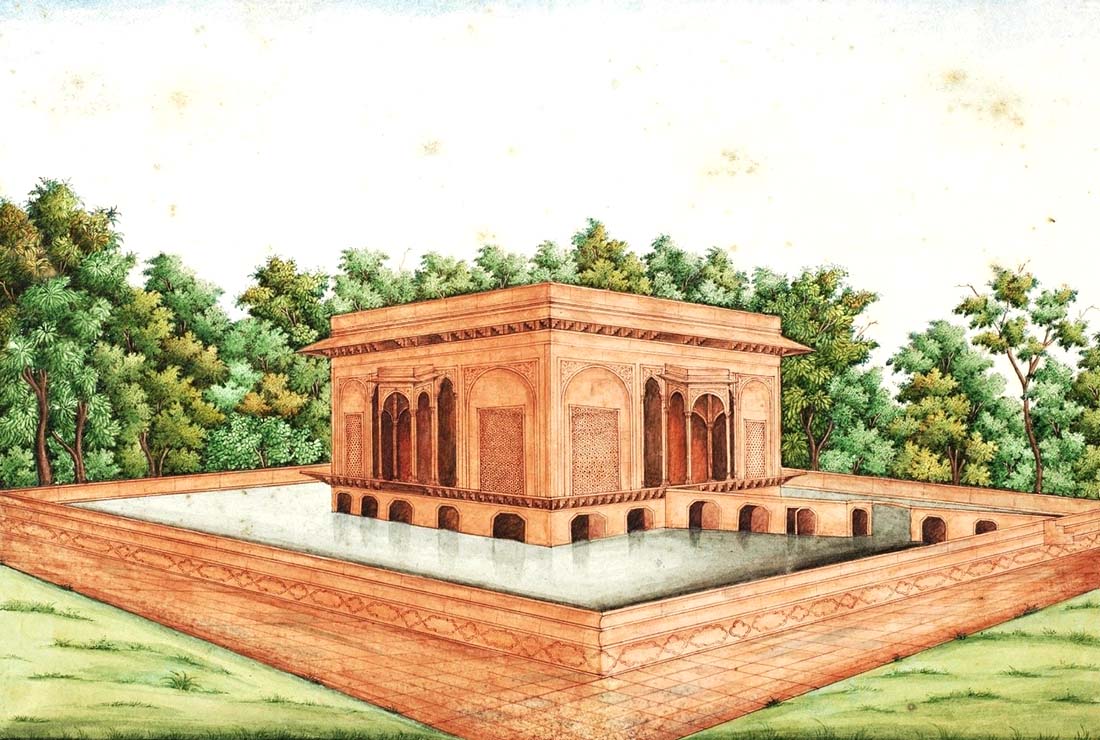

The Red Fort complex was endowed with several gardens, chief among which is the Hayat Baksh Bagh or the “life bestowing garden”. This garden was built on the concept of char bagh or pleasure gardens, an important characteristic feature of Mughal architecture. Two beautiful marble pavilions, called the Sawan and the Bhadon stand opposite each other on the north and south ends of the garden. A red sandstone pavilion called Zafar Mahal, stands in the middle of a large water tank at the centre of the garden. It was built in 1842 CE by Bahadur Shah Zafar. The water for the tanks and fountains of the garden was provided by the Nahar-i-Bahist.

Zafar Mahal. painting by Ghulam Ali. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The southernmost residential building is the Mumtaz Mahal, which was partially constructed with marble, i.e., only the lower portions of its walls and pillars. After the British took over the Red Fort, this building was used as a prison for some time. In 1911, the British turned a portion of the building into a museum during the visit of King George V. After Independence too, the building remained as a museum, under the Archaeological Survey of India, displaying Mughal items. This museum has, however, been shifted to another building now.

The Decline of Mughal Power and Grandeur

Starting from the 18th century CE, the power and prominence of the Mughals steadily declined. Aurangzeb’s successors were weak and inefficient and the Mughal empire soon became only a shadow of its former glory. It was remarked in jest that the authority of Emperor Shah Alam (1759-1806 CE) extended only from Red Fort to Palam (a village in Delhi)! The Red Fort, the symbol and seat of Mughal power, was gradually shorn of its magnificence, both by external invaders and internal decay. The later Mughal rulers stripped and sold away many of the riches of the fort. Nadir Shah invaded Delhi in 1739 CE and carried away the Peacock Throne and the Kohinoor, along with other riches.

The Uprising of 1857 and British Reprisals

A photograph of the Red Fort taken in the aftermath of the Uprising of 1857 by Major Robert Christopher Tytler & Harriet Tytler. Image Source: British Library

The most definite blow was, however, dealt by the British who took over the fort after the failure of the Uprising of 1857. During the uprising, the revolutionaries displayed a “centripetal impulse to congregate at Delhi”, and the Red Fort and Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah together became an important symbol for the rebellion. Thus, after the uprising was crushed, the British spared no attempt to destroy and subvert the prominence of this structure. They demolished many structures inside the complex and converted others into military garrisons. Bahadur Shah Zafar was arrested and tried in the Diwan-i-Khas and exiled to Rangoon. While some precious jewels and treasures of the fort were looted by the pillaging British troops, others were extracted and carefully shipped off to England.

Under the British

Despite such wanton destruction, the British did not manage to diminish the significance that the fort and the city of Delhi held in the imagination of the people of Hindustan. Instead, they attempted to appropriate it. The Coronation Durbar of December 1911 was marked by the visit of the British King George V and Queen Mary to the Red Fort. They made an appearance to the public from the balcony of Musamman Burj in the manner of the jharokha darshan of the Mughal Emperors. It was also announced in the Coronation Durbar that henceforth Delhi would become the capital of British India instead of Calcutta.

A Bastion of Anti-Colonial Struggle and a Symbol of Sovereignty

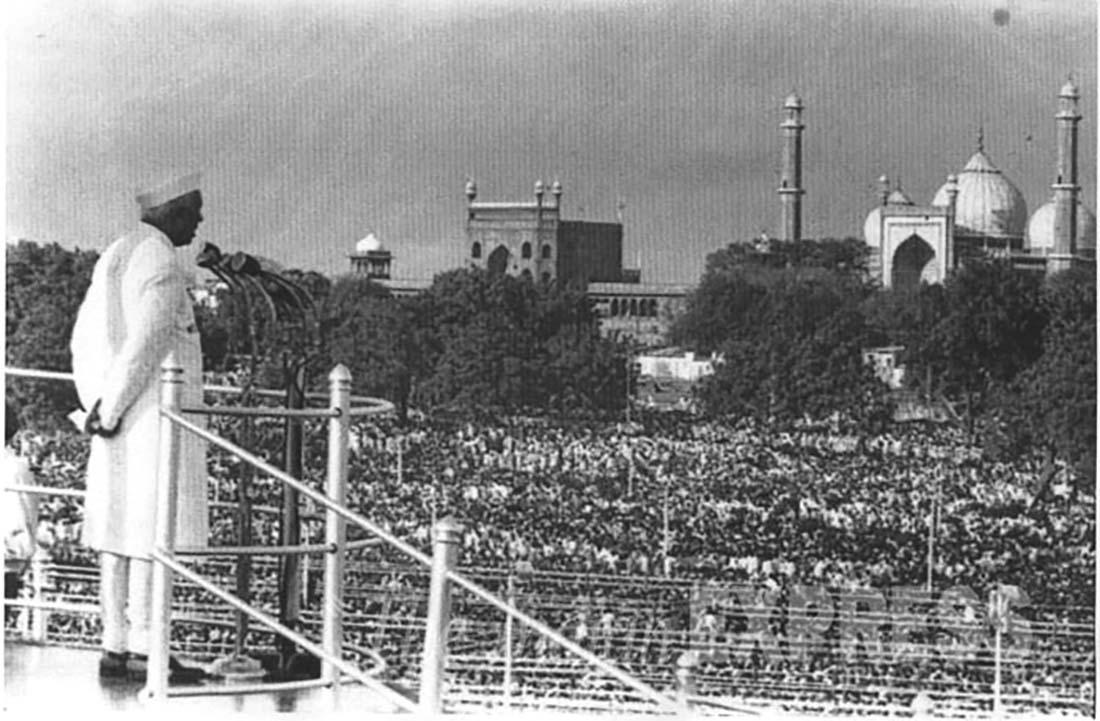

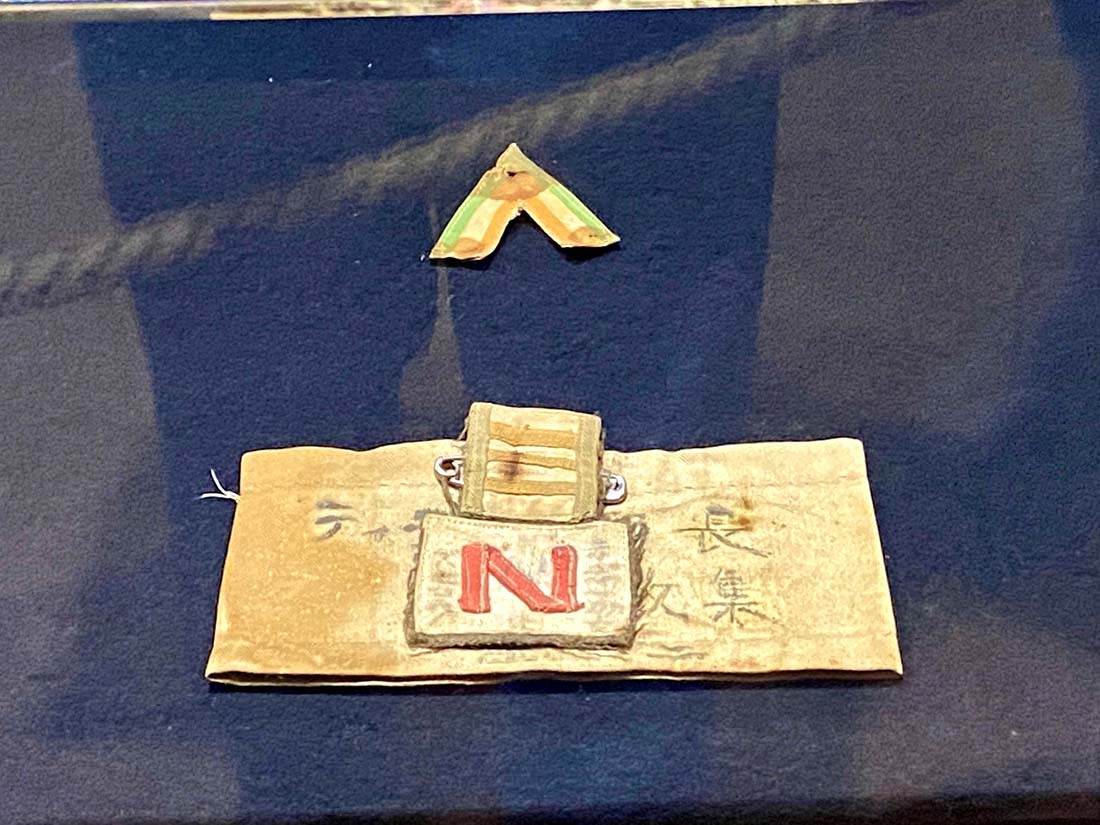

The iconic monument once again came to the limelight at the height of the struggle for Indian Independence. The Azad Hind Fauj or Indian National Army was organised by Rash Behari Bose and revived under the leadership of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose during the early 1940s. Netaji gave the famous call, “Chalo Dilli” with the aim of attaining full freedom from the British Raj. After the defeat of the INA at the hands of the British, its soldiers and officials were captured, charged with treason and tried at the Red Fort. The trials resulted in a massive surge of nationalist sentiments and the Red Fort re-emerged as a symbol of anti-colonial resistance. The logical culmination of the nationalist upsurge was reached with India attaining Independence on 15th August 1947 and the unfurling of the tricolour at the Lahori Gate of the Red Fort by Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru, the next day.

Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru addressing a crowd at the Red Fort, 16th August, 1947.

After Independence, the Red Fort came under the authority of the Indian Army and remained so till 2003 when the Archaeological Survey of India took control over major areas of the fort complex. Thereafter, the fort was declared as a World Heritage Site in 2007.

Badge of an INA soldier, displayed at a museum at the Red Fort.

The Red Fort, continues to be an enduring symbol of India’s sovereignty and freedom. Today, several museums namely, Indian War Memorial Museum, Subhash Chandra Bose Museum, Yaad-e-Jallian, Museum of 1857, and Azadi Ke Deewane, recount stories of India’s struggle for freedom and display a melange of memorabilia associated with it. Every year, the Prime Minister addresses the nation from the ramparts of the Red Fort reaffirming the continuing significance of this iconic structure in the political and cultural heritage of the country.

The Tricolour flying at the Red Fort. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Government of India

Government of India

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.

Recognizing the ongoing need to position itself for the digital future, Indian Culture is an initiative by the Ministry of Culture. A platform that hosts data of cultural relevance from various repositories and institutions all over India.